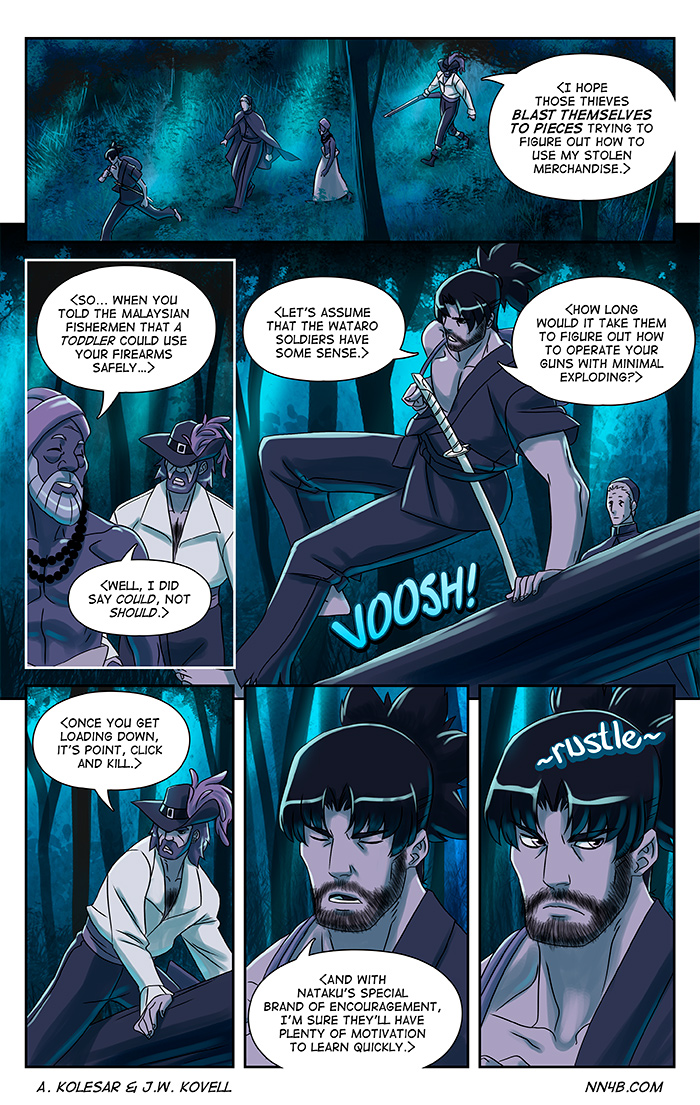

Back to Genchu and his travelling troupe for a little bit of second amendment conversation.

I’m trying to get back to updating the comic Sunday night instead of Monday night, it’ll happen! I’ll try not to be too distracted by E3. I’m curious to find out how many of the games I’m excited about will get pushed back to 2017!

Published on by Alex Kolesar

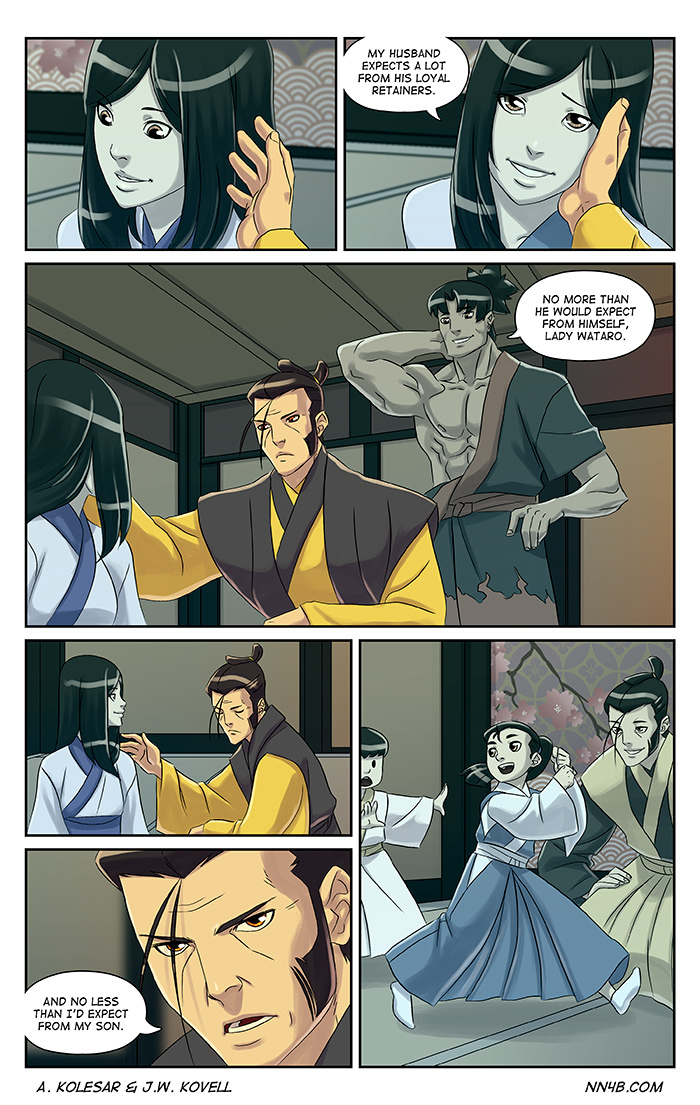

He’s got 99 Jimmies… and someone just rustled one of ’em

The vooshing sound in this case is the reference flying over my head. Would someone care to elucidate?

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/that-really-rustled-my-jimmies

Thank you kindly, good sir.

You magnificent charles you

Hopping over logs is for plebs. Genchu VOOSHES over logs and they darned well better like it!

I’d like to imagine that Ken is somehow responsible for that log.

“Point, click and kill”? Nice dialogue for feudal Japan. 😜

Would you prefer the original Portuguese?

Why, yes, I would. 😎

Think of it as Portuguese, translated to feudal japanese dialogue then translated back by google translate and finally “massaged” by a guy who simply figured “this is what they probably said… probably”

Gun control? Easy, same as kenjitsu. Business end towards enemy.

Stick em with the pointy end?

Ooh yes! I love this group! I’m glad we get to see what they’re up to now.

Let’s hope for a quick resolution to all this.

Soldier: “General Nataku, my gun won’t fire!”

Nataku: “Why not?”

Soldier: “I don’t know.”

*Nataku puts his eye up to the barrel*

Nataku: “Okay, try again. Let’s see what’s wrong.”

That would be perrrrrrfect

But unlikely. Shame.

Last panel: squirrel? Or ninja squirrel? Better safe than sorry!

~GUNS~

making killing easy since 1500

there was no Malaysia during this era. There were Malay Kingdoms, sure, no Malaysia

Alex and I actually discussed this point. After extensive Wikipedia “research”, we determined that, as with most of the comic, the original Portuguese or Japanese dialog has been translated for modern English audiences.

See also: Canada, “Fire!” Instead of “Shoot!” for some scenes featuring archers, and hotdogs.

You’re welcome

Well, that makes everything I’ve read so far make a lot more sense

Also, since it’s alternate reality, their Malaysia could exist sooner. Maybe it’s all Rrrricky’s doing.

Wait wait wait are you saying that this comic is written in multiple languages and changes depending on the country you’re in??? Or am I just very confused?

Aye, the shootin’s easy but it’s the loading that’s a right bastard to figure out.

Clean the barrel, light the fuse, pour the powder, put in the bullet and the wadding, ram it in there with the ramrod, arm the lock, then it’s good to fire.

I’m pretty sure a toddler could use firearms safely. Just don’t give ’em bullets to play with.

While I love me some bad guy power-ups to liven up the lives of Our Heros, it’s worth pointing out a few … complexities … with “point, shoot, and kill” using historically-accurate guns.

First off, what sort of guns ARE these? Despite the line drawings (see page 629) being somewhat vague, the only type of gun that could have been sold to Japanese without them *already* knowing all about guns in warfare is a matchlock arquebus, introduced to Japan in 1543. The Japanese called the arquebus the Tanegashima (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tanegashima_(Japanese_matchlock)), took but little time to learn how to use and make it, and employed it enthusiastically. It had a major effect on the warfare of the Sengoku period: the mass-mobilization of conscript, peasant armies, and the concentration of power in Oda Nobunaga’s hands.

So, what’s a tanegashima? It is a mass-produceable matchlock firearm, capable of shooting once in 1-2 minutes, approximately once per 10-15 shots from a skilled archer. Effective ranges are 80-100 meters (again mass infantry or cavalry formations), 50 meters (man-sized targets), or lower (well-armored targets). Training takes only a couple of months – a major advantage over the bow. The gun has no bayonet, so it was only about as useful as a club in melee. The lit match makes it almost impossible to conceal. Smoke from firing makes deliberate aiming impossible for minutes on end, but the Japanese employed measured strings that greatly reduced the problem against massed targets. Rain always causes problems for ignition of matchlocks, due not just to the match, but also to the powder getting damp. The Japanese did develop techniques to fire in the wet, with some partial success.

Critical to effective use of the tanegashima include:

– Figuring out how to bore barrels. The Japanese had little problem with doing everything else required to mass-produce firearms, but this took foreign advice and a few years. Advantage: the most powerful daimyos, because they had better foreign contacts and could hire more and better blacksmiths.

– Sourcing gunpowder, in particular saltpeter (potassium nitrate). This is not a major issue, but it takes skilled advice and economic mass mobilization.

– Obtaining lots of conscripts. The tanegashima was a weapon used by peasants, who were conscripted en masse. This greatly advantaged the most powerful daimyos, because they could conscript more peasants. The Sengoku did not last long enough for peasant uprisings using guns to become an issue, but I can see a sufficiently radical Japanese commander leveraging strong local support to raise a formidable tanegashima-armed militia.

– Figuring out two things: a) How to keep gun-armed troops from being overrun with cold steel, and b) how to keep up rate of fire. The first problem the Japanese addressed by supplying personal shields (pavises), placing troops behind barriers, and – above all – by surprising enemies not used to such warfare. The second was resolved when Oda Nobunaga’s men learnt volley fire and fire by groups. Other important Japanese advances included appropriate use of bigger hand-guns in both mobile warfare and fortifications. Pistols, however, never seem to have become a big thing.

How do you respond to the introduction of guns to warfare? The Japanese, Koreans, and Chinese had a lot less time after 1543 and before the Japanese invasion of Korea and the end of the Sengoku (1592-8; 1603) to figure this out than did the Europeans, and their response therefore never became as sophisticated. The European responses to handguns, or or before the year 1603, included:

– Stop getting ambushed. Arquebuses/tanegashima have very strong alpha strike, especially at close range, but are much inferior in sustained rate of fire or long-range dueling.

– Fielding cannon. The French did this to great effect in the whole of this period, but learnt a bitter lesson at the Battle of Pavia (1525): Don’t mask the guns!

– Up-armoring your assault infantry and heavy cavalry. The French in particular won a lot of battles this way. Guns made light armor less useful, but it was only well after 1603 that the velocity of shots from guns rose enough to make plate armor useless. Problem: plate armor is heavy, expensive, and requires both highly skilled blacksmiths and abundant iron and fuel. France had all of these things. Most other places didn’t.

– Archers. The English had abundant skilled archers, and kept on employing them with fair success throughout this period. In Japanese conditions, archers might be most effectively employed in long-range duels of missile troops, mobile shoot-and-shoot skirmishing tactics before the main clash of infantry (perhaps aided by the presence of trees and other cover), indirect fire – which is less effective than direct fire for archers, but almost impossible for tanegashima-armed troops, and night warfare (aim at the glow of the matchlocks). Gun-armed troops will want to advance en masse, get close, and wipe out the archers with volley or platoon fire. The basic problem with archers is that they are really hard to replace!

– Mobile, Swiss-style pike tactics. Basically, get a lot of brave men who are willing to charge home against gunfire, taking the casualties needed to close the range and win in melee. If the enemy knows about volley fire, you will need to send forward skirmishers to draw fire before the mass charge. Swiss tactics are particularly effective if the other guys don’t have enough pikemen, and have been lured away from fixed or temporary fortifications. Remember: It takes more than a line of stakes in the ground to stop a pike advance.

– Pike and shot formations – the famed Spanish tercio, victorious on every inhabited continent. Combine swords, pikes, and muskets in a combined-arms formation. Drill incessantly. I suspect that this would be extremely effective in Japanese conditions.

– A war of fortifications. This was a major feature of European warfare, because they had enough time, starting in the early 1400s, to progressively upgrade their strongpoints to accommodate cannon and handguns. Less appropriate in Japan.

– Cavalry. Suitably armed, trained, and equipped, cavalry can do the following things in gun warfare:

– Shock action against unprepared infantry. The Japanese knew a lot about this, but (like the Europeans) took a while to appreciate that greater preparation was now necessary for a charge to succeed. Preparation might take the form of distractions, frontal engagement with your own infantry, or cannon fire. Once the arquebus-armed infantry start firing, they can’t see you charge.

– Mobile response. Arquebus-armed infantry are something of a cumbersome tool: Strong, but slow and difficult to use flexibly. Well-trained light and medium cavalry, by contrast, can take advantage of opportunities or shore up critical points.

– Scouting. This is always rule #1 in warfare. Gun-armed Japanese tended to win because a) the enemy didn’t know enough about gun warfare, and b) were out-scouted.

– Rate of fire. Pistol-armed cavalry had some surprising successes against arquebus-armed troops, because they could canter up, unload their pistols quickly, and scamper before the infantry could get enough bullets into the air in response. Or, they could charge after softening up the foe (this requires excellent cavalry!). Both options worked especially well if the enemy infantry also had to deal with your own infantry.

Lots more to be said, but this should give you some thoughts on what might change in the world of No Need For Bushido.

Slow clap for the epic “too long, read anyway.” Props.