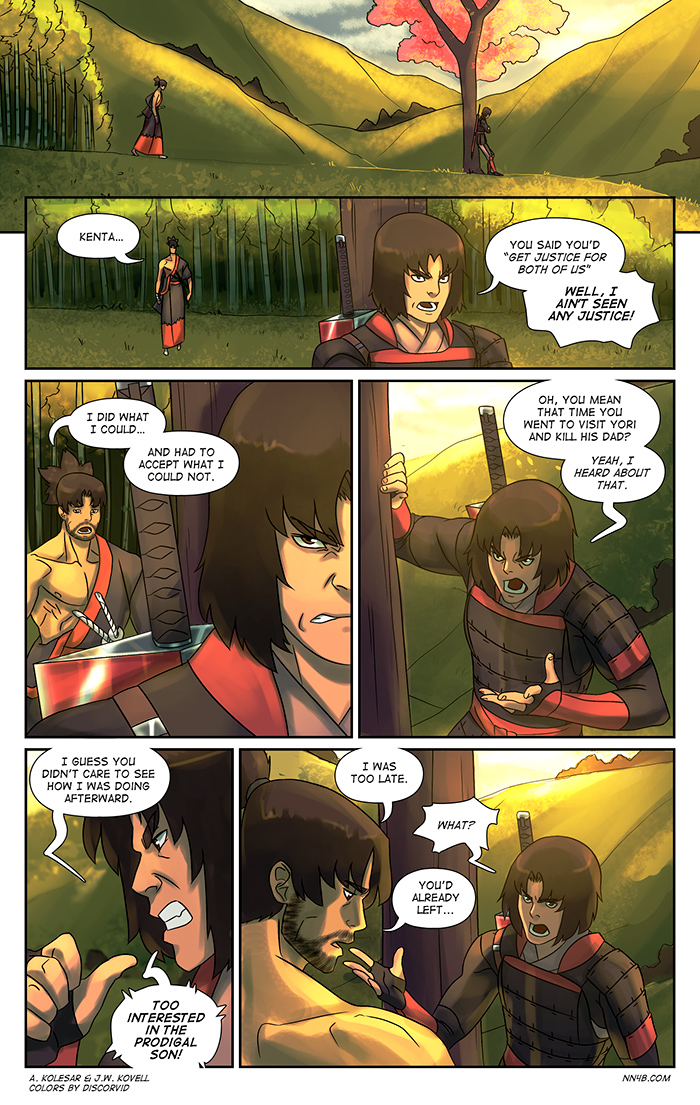

Hey, Ken, are those real human feelings I’m seeing behind your concrete exterior?

So Rurouni Kenshin has potentially been the most influential piece of fiction in my life outside of Star Wars. It awakened in me a continued love of Japanese culture and history that became the impetus for starting No Need for Bushido. A day after I posted the previous comic page, this hit the internet. Nobuhiro Watsuki, the creator of Rurouni Kenshin, was arrested for owning child pornography (apparently live videos of middle school aged girls). I find this reprehensible, and since then I’ve found it hard to even THINK about the series that, up to this point, I’ve treasured.

I’ve been trying to wrap my head around the seeming contradiction between a man who seeks out material that sexualizes girls too young to fully understand what’s happening and the narratives he’s woven that encompass redemption, understanding, and overcoming a lack of self worth. But the truth is maybe those themes don’t align with the personal beliefs of a man I can no longer admire. It’s not unheard of for terrible, or otherwise broken people to produce powerful, transformative fiction. Still, I think we all want to believe that when we cherish a piece of media that radiates positivity and hope, we want t believe it comes from a person that embodies those messages.

But when a creator does not match up with the work, for some people it can become impossible to view the work in the same light, and I find that I’m one of those people. I used to love Ender’s Game, but now its messaging reads as far less inclusive after learning of Orson Scott Card’s social political views. Likewise, the seemingly innocent and wholesome relationship between Kenshin and Kaoru was one I never used to question, especially as it’s never sexualized in the narrative outside of some very light innuendo, and nothing as bad as what you see in 98% of other anime. But now I just keep thinking, Kaoru was 17, Kenshin was 28. Did we really need an 11 year age difference between these two, especially with her in the teens? Was this the trappings of a teen-focused genre shoehorning in an older main character to work with the historical timeline? Or was it a preference of Watsuki’s? Regardless of whether such an age discrepancy was considered acceptable in 1870’s Japan, the story itself was written in 1994, and it was a manga series meant to be sold to teens.

Having said that, I don’t want to view the relationships in Kenshin as anything less than pure and positive, and a great deal of the story’s messaging revolves around that. Nor do I not consent of fully grown adults with decade age gaps falling in love. After all, we only get one shot on this blue sphere. And I keep telling myself that manga artists have teams with editors and assistants who collaborate on the writing and story. So maybe it’s a similar situation to George Lucas, a man who clearly couldn’t have made Star Wars the success it was on his own. Maybe Kenshin’s narrative triumphs aren’t entirely of Watsuki’s own makings and I can still feel good loving the series.

But the truth is I doubt I can ever go back to my unconditional love for Rurouni Kenshin. Yet its themes of hope, redemption, and finding one’s inner purpose are timeless beyond any particular piece of fiction. Even though I may never be able to reflect on the series with the same level of reverence, I’m very glad for the many philosophies and passions it instilled that I will carry with me for the rest of my life.

But, seriously, GODS DAMMIT!

Published on by Alex Kolesar

People still watch Chinatown, when Roman Pulanski was revealed to have committed statutory rape.

And the big reveal in the movie is incestual rape, so…irony? 💀

How do you cause the font/background color effect in your comment to hide text?

It’s the Spoiler tag, using standard old-school HTML. text here , but with no spaces in the tags. Same goes for (bold), (italic) and

(strikethrough). 😎True. But Chinatown is a pretty dark film. the Kenshin manga is bursting with themes of hope, renewal, redemption, and finding self worth. Which makes it harder to enjoy the series knowing the creator has recently supported practices that take advantage of those who can not properly consent. Weirdly, I’d probably find it easier to appreciate a film about a serial killer if I found out the director had murdered someone (not that I’d want to support such a director).

Why, that’s positively heartfelt, coming from Ken!

Anyhow…

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/9a81f0e81431e0f7e0d182a8fdb768c2d2fc4935e6add82fcf9e5747c717db5b.jpg

The one thing to me that was untouchable and classic. Although (in the OVA) there was the obvious innuendo for Tomoe to be ‘the sheath for his sword’. Bit cringe worthy metaphor. I’m now wondering if it was intentional. I will forever look weird at swords in anime when there are children involved.

I will say this Alex, Im glad RK exists for the fact that your comic got created. Having been a avid reader of this comic since the early 2000s it has just as much nostalgic value to me as any anime I watched in Highschool.

So even tho I cant really pick up Kenshin any more. At least I have no need for boshido as a safe subsitute

I am not disregarding how you feel about all that, but I think you are commiting a common logical mistake. No person is :

a.) fully consistent in his/her morals

b.) defined by a single thing they do in their life

He may be (not necessarily is) both a pedophile and the great author you loved, who put the themes he believes in to his work. I think that both are possible at the same time and there is nothing contradictory about that.

Exactly. Not every celebrity becomes the next Charles Manson just because he/she enjoys something that is generally disapproved of, but likewise, monsters sometimes take the unlikeliest of guises. Do we stop enjoying Tarantino movies because they’re published by The Weinstein company? Are all House of Cards fans now pedosexuals by association?

I’d like to think I made those points in the text! My issue is that even though there is a level of separation between work and author (good writers can write from character perspectives they do not share or agree with), it’s hard, if not impossible for me to view his work without the context of my knowledge of the creator. The worst part about it is despite how relentlessly positive the messaging in Kenshin is, its creator knowingly possessed materials that exploited young girls.

If Watsuki were just into cartoon porn featuring middle schoolers, I would roll my eyes, maybe talk about how I dislike that Japanese media sexualizes young girls, but instead he was supporting something that directly harms other individuals. Knowing that impedes my ability to enjoy the series, even if it’s not reflected in the series in any obvious way. I still WANT to love Kenshin unconditionally, I just can’t disassociate it in my mind now, and it’s immensely frustrating.

It’s not a perfect analogy, but it reminds me a bit of the issue of whether to use medical research that was derived from experimentation on humans in Nazi camps. Should one separate the benefit from the source or how it was obtained?

It’s not an answer to all situations, but if I’m tempted to think after-the-fact in coldly pragmatic terms only, I’m also cautioned when I recall a time when the Philistines, David’s enemy, had control of Bethlehem. David made the off hand remark, “Oh that someone would give me water to drink from the well of Bethlehem that is by the gate.” Three of his mightiest warriors heard this and took it seriously. They managed to get into occupied Bethlehem, got the water, got back out, and offered the water to David. But David refused to drink it. “Far be it from me, O LORD, that I should do this. Shall I drink the blood of the men who went at the risk of their lives?” So instead of drinking it, he poured the water out as an offering to the LORD. He couldn’t separate the benefit of the water he had wanted from how it had been obtained and the potentially lethal risk to his men. David understood something that went beyond after-the-fact pragmatism.

p.s. In the case of R.K., I’ll acknowledge that one way it may not be analogous is that the creation of R.K. may not depend upon these problems of the author in the same way that my examples directly depended upon specific objectionable actions or problematic risky choices. Yet, I wanted to convey that I can understand how it can become difficult to separate and untangle matters in these situations.

Damn… gave Ken a personality in the matter of just two panels.

Ken’s always had a personality! It’s just been mostly one-note.

From all the characters, I thought him least likely of personal development, while he’s also the most overdue.

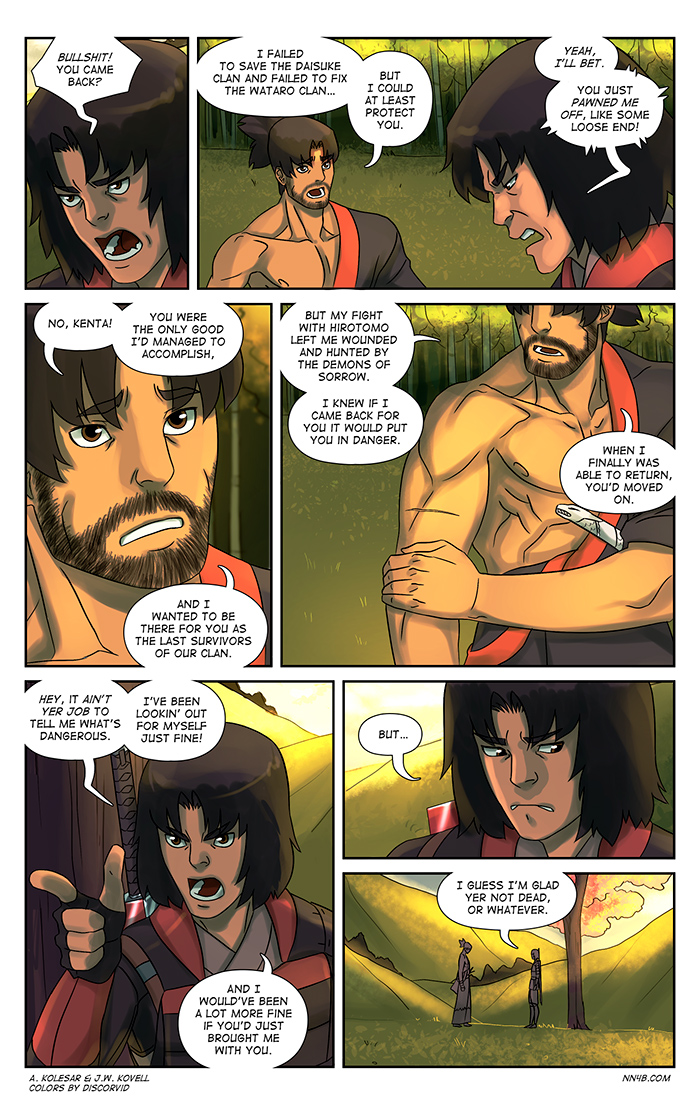

If they’re technically both Genchu’s step sons, does this mean they’re related now? It would be fun to see Ken having trouble acknowledging Yori as his ‘brother’, while at the same time playing the ‘who’s the favorite step son’ game. Kadoosh is still my favorite game, but boy do they need a father figure, Ken more than anyone.

What I’m saying is I like this softer side from him, although it will probably never be mentioned in front of the others (unless in Hellsing Ultimate chibi style :-3 )

If they’re technically both Genchu’s step sons

I think that’d be jumping to conclusions a little bit! At most he’s an honorary uncle to Yori. And whatever relative to Ken, since he was adopted into the Daisuke clan…? Is there a backstory to that, I wonder. Nah, Genchu must have already filled his backstory quota by this point.

Genchu is definitely a fatherly/paternal figure to both Ken and Yori!

All right then!

Come on, we know who he is!

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/0125a9c4bbdc08ee2afe4d82a3866e0aa5b7352e8a293d9b012977e93ac290da.jpg

I get where you’re coming from. For me, it was also Orson Scott Card’s work that I had to take a step back from after seeing what he truly stands for, which really sucks since I loved reading the Ender and Bean series, but I can’t look at them the same now that I know the lens which he wrote them through.

Unfortunately, our heroes, our idols, are just human. They’re far from infallible and we can’t treat them as such. We must hold our heroes to the same standards we would hold anyone else.

I don’t think I was that surprised, because while Ender’s Game was good, the later books in the series felt really preachy to me. It was as if he wrote the books just to voice his opinions.

Speaker for the Dead was pretty good, but they got weirder from there. The Ender’s Shadow series started off well, but quickly devolved after the first book. It’s too bad Card can’t separate his politics/religion from his storytelling.

aww, lookit that, they’re bonding ^^

;_; Gods Damnit, indeed. And there are a lot of December/May and December/Mayfly stories out there: all of them just got a hell of a lot harder to watch. I’m so, so sorry.

december/may?

older/younger pairings.

ah, of course.

For what it’s worth my problem is more that an actual child is hurt in the making of child pornagraphy as opposed to something like hentai where you can draw a child character but have them being voiced by an adult. I still don’t understand the turn on and find it creepy but as long as no actual children are hurt I can not bring myself to object to it.

If he had confined him self to hentai I wouldn’t have a problem.

In another note have you ever heard of the Death Of The Author

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Death_of_the_Author

The reason I brought that last one up is that Watsuki’s authorial intent is COMPLETELY divorced from how you feel about his works.

personally I don’t see why some people think loli hentai is all that much different then child porn. they’re still getting their jollies watching an underage character get sexualized. it’s a slippery slope in my book.

Some couples like to roleplay one member taping the other. You and I may find it creepy as fuck but so long as no one is ACTUALLY getting raped who are we to object just because it isn’t normal? It all comes down to consent. And speaking of slippery slope what about stuff like Game Of Thrones? Under the way you interpret the law such works could not be written even though they clearly have artistic merit because some people will get their jollies off on them.

fair. most hentai is rape. And yes, I have looked to find similar live action porn. non consensual stuff, because of watching too much hentai like that. and yes I do see that as a sick perversion of my mind that I wish i had not gotten. So I do still stand by my point. I do after all, speak from personal experience. Finding interest in one thing will lead you to more and more until you finally hit your hard point and realize it should have been a ways back.

I see kinks as a stair case and there are just certain steps you should not reach. certain things that are just plain deplorable even if there are just “cartoons”. Guro is a good example. that shit is fucking sick.

Question: With drawn “kids” how do you prove if they are kids or adults? You can give them the proportions of a 30 year old woman and call them two, or on the flip side give them the porpotions of a twelve year old and call them 29. In the end it comes down to the fact thst you are policing thought rather than actions.

policing thought? Okay I’m not entertaining that argument.

If they look like a child, and they act like a child, and they are sexualized, then it’s sick. real life or drawn.

I never said it wasn’t sick. I am just saying it is possible to have sick thoughts and not act on them. Are do you disagree with that conclusion?

Following on from that a drawing does not hurt, rape, or molest, a person and it is ludicrous to suggest otherwise.

On those points I do agree.

“Don’t stop not dying, Genchu!” 😎

Genchu: “Do we hug now?”

Ken: “Not unless you want my sword to hug your rib cage!”

Genchu: “That doesn’t… wouldn’t that be the other way around?

Ken: “Don’t question my mouth words of course not, cheese doodle!”

I don’t know about the romances. To me, the differences between Kenshin and Kaoru felt more to emphasize how he went through the Bakumatsu, while she was still too young to experience it. She’s also weirded out about it at first, but I guess for as long as they played husband and wife for everyone, they eventually said screw it and got married. Misao also felt more like that teen girl in love with the older man because he’s handsome, cool, etc.

Also, not all the relationships had a decade difference with younger women. Tomoe was apparently 18, while I think Kenshin was younger when they got married. Also, Sano goes for the older Megumi. So it doesn’t seem his fethises were rampant, and the other ones can be seen in a more legitimate light.

So, in the end, I think I can keep my feelings for the author and the series separate, and can come up with my own theories about how the romance developed… but still, Gods dammit. And I found out AFTER he apparently started the series up again.

Ya, I agree with you, and I’m rather sad because I didn’t even get to read any but the first few pages because I kept putting it off. damn, I was all happy for it to return. sigh.

Yeah, my biggest issue with this whole situation is that Watsuki had ownership of material that exploited young girls at an age when they would not be able to full grasp what was being done to them. Japanese media has a problem with sexualizing underage girls, but if it’d been found that he had some hentai stuff, I say “well, okay, that’s not great, but no one was harmed here, outside of the perpetuation of a systemic societal issue.”

The portrayal of the relationships in Kenshin are pretty much all unanimously wholesome and come from a place of caring for each other. I hadn’t put much thought into the age difference of the lead characters until this incident, and now I can’t completely ignore it, even though Kenshin and Kaoru’s relationship is never emotionally of physically abusive (outside of Kenshin leaving her to go fight Shishio, although he does eventually comes to realize that did more harm than good).

I had also read the first couple of chapters of the new Hokkaido arc and was enjoying it immensely.

It would appear that Kaoru’s age probably hasn’t got to do with the creator’s preferences, because… she’d be too old to appeal to those preferences (based on the quotes here). Which, yes, that’s even more disturbing in its own way.

I can understand if you feel torn between wanting to support a work you love but not wanting to support someone who does morally reprehensible things. At least with a movie there is a whole cast and crew who ALSO get paid royalties with a book not so much. Damn what are the economics on buying used. I think they still support the original author otherwise I would just do that. Are we sure this quote is from him. Given Japan’s messed up legal system there is a small but real chance this a lie. But given a quote from Watsuki I am not holding out hope.

i buy a lot of manga used, pretty sure that only supports the company or person selling the book. I dont think anyone get royalties on resell. only the first time a book is sold new.

More a matter of separation than anything. Separate the worth of the work from the creator and judge it itself on its own merits, not clouded by what the humans involved did or did not do in reality. Incidentally this applies to Ken too.

That age gap never bothered me, I don’t think I ever paid attention to it really, since there wasn’t heavy romance. I totally get what you’re saying though, but I will say this. A few of the US states, 16 is legal. Many countries in europe, 16 is legal. I heard Japan, even today, it’s puperty. (yikes. just looked it up. Google says the legal age of consent in Japan is… ready? 13. THIRTEEN. so, ya. wow.)

Now, personally, I think 20 should be legal adult age, as eighTeen nineTeen are still well, teenagers, and from my experience talking to them, they’re not all that mature, even if girls mature faster then boys.

To me, 16-18, not really much difference. I’m sure there’s plenty of historical accounts of late 20’s people with mid teen people.

Also 18 year olds are still in school and this means by 18 being considered adult you can get into porn while in highschool, and buy cigarettes while in highschool and heck, then we have the issue with them selling to younger kids.

I’m not really sure where I’m going with this about the 17-28 gap. I guess a lot of young girls at that age look up to older men, to me it’s really not that farfetched. I dont look at the time things were written I look at the time the story takes place. and I think even in modern japan that may be fine, I haven’t researched them a lot recently. as my hobby interests have been more sci-fi and medieval combat history as of late.

As for Rurouni Kenshin, well. I got a bunch of posters I haven’t hung up yet. I may still do so because dammit, it was a good story. I will probably still watch the anime again at some point but now it’s pushed back on that date.

I’ll still respect the work, but I am disappointed in the man.

Really, that last sentence embodies my take on the situation.

Well, whether the relationships in Kenshin are creepy or not (and I still think they are portrayed in a totally wholesome context), knowing that the person who created those fictional relationships was also willing to support those who would sexually exploit young girl for profit makes it very hard for me to embrace the series as I once did. Even though Kenshin and Kaoru’s relationship seems totally healthy, and filled with love, caring, and devotion, now that I know Watsuki supported child pornography, I can not help but think of that the franchise revolves around a romance between a 17 year old and a 28 year old. This is why I’m so upset, as the creator has forever diminished to fully embrace his work, as much as I’d revered it. I honestly would have a hard time even recommending it to someone now, even though I still think it’s a great series and hugely influential on me.

All very fair points. There’s an old adage that once again makes great sense.

Never meet your heroes.

Basically, when you truly love the work someone has done, you forget how flawed humans can be.

I love kevin’s sorbot’s hercules. I enjoyed his campy acting. but there’s one small thing I think he’s an idiot about.

Sometimes it’s better to not know anything about the artists we fall in love with.

I was going to say something witty until I read the news about Nobuhiro Watsuki. That is…a lot to absorb.

I forgot how young Ken was, sooo much teen angst!

Honestly, Ken should do a guest appearance on Wild Life as one of Cliff’s not-friends.

He’s 20, still young enough to ANGST OUT.

Aww look who missed his surrogate daddy

OK just hug now and get it over with.

Werewolf vs. Drunken ronin warrior. Who will win, depends on if Ken wants a wolf loin cloth or if Cliff wants to steal Ken’s sake and sword.

Given that RK was published in 1994, it’s also possible that Watsuki had no involvement with pornography at all at the time, and that this is something more recent (the only dates I could find said “possession since July 2015). I don’t want to diminish the seriousness of his actions or the effect this will have on readers of the series (RK was my first manga and still my favorite), but 20+ years is a long time, and people change, sometimes for the worse. It’s possible we’re projecting his “interests” onto the Kenshin/Kaoru relationship, though of course it’s also possible it’s the result of those interests.

Either way, wow. Damnit indeed.

Yeah, there’s certainly a possibility that the original series run predates any activity that would be considered illegal today. And I don’t want to project a dark intent onto the Kenshin/Kaoru relationship, as I honestly don’t think it’s portrayed as anything other than wholesome and positive in the manga. But in light of events, I can’t help but be hyper aware of that age difference. There’s also the 10 year age gap between Misao and Aoshi, but at the same time they never have a formal romantic relationship in the comic, and Aoshi seems to treat Misao more as a little sister (and rightfully so), while she clearly has romantic feelings toward him. Although it never strays into creepy territory, and everyone referring to their relationship uses language like “someone you care about”, which is vague enough that it never really bothered me.

Honestly, the fact a person is aroused or attracted to a specific age group doesn’t bother me (people have all sorts of weird kinks like that and far beyond the sense of logic), its how they choose to handle that side of themselves which is important. This isn’t minority report, people still have to actually commit crimes before being judged.

As long as he hasn’t directly molested a kid or something, simply viewing it isn’t a terrible thing in my mind. I strongly disagree with it, and the creation of it is illegal as it involves a minor, but consumption of it isn’t as bad. Its still illegal and him paying the price for it is acceptable, but I don’t see that alone as a damning characteristic.

I don’t wholey disagree with you on any particular point. Everyone has the potential to redeem themselves, and we shouldn’t be judged based on what we find stimulating. And it’s also not entirely clear to what extent he supported child pornography or had ownership of it based on any of the news stories, just that he definitely did (and considering the police weren’t even initially investigating him but followed a trail of evidence to him, it suggests his ownership of the material was in no small amount).

My big issue here is that I, personally, cannot entirely separate the work from the author. Since he supported child pornography to some degree, when I reflect on the series, any relationships involving teenage girls interested in grown men in the comic bring to mind that the author has a less-than-wholesome preference that MAY have influenced what I used to view as positive depictions of romantic relationships. And I’m not even saying that they aren’t still positive depictions of relationships, but now when I read the material, I have doubts about the author’s intent that my brain can not just turn off, and that is why I’m frustrated and disappointed. Was he trying to subtly normalize his sexual preferences? Was it an unconscious decision? Now that it’s clear the author had sexual interest in middle school aged girls, was depicting a healthy relationship between a similarly aged girl and adult man a means of fulfilling a fantasy? Maybe not, probably not, but I can’t help but wonder.

To be fair, if Rurouni Kenshin did not revolve around a relationship between a 17 and 28 year old, I would probably be able to continue loving the series unconditionally, while just choosing to no longer support the creator on moral grounds. If this same information in no way affects how you view the work, there’s nothing wrong with that. The work and the person who created it can be evaluated independently of one another.

I’m reminded of “Le Morte D’arthur,” a.k.a. “the Death of Arthur.” It’s the classic and more or less “original” version of the stories of King Arthur and the knights of Camelot. The inspiration for T.S. White’s “Once and Future King.”

It’s also written by Sir Thomas Mallory, while the knight was in jail for rape. The book (a story about imperfect heroes striving and failing to achieve achieve salvation and redemption) was Mallory’s plea to G-d for forgiveness.

it is? Hmm, interesting. I’ve noticed it’s rare to find an ancient hero, a la hercules or beowulf or whoever, who while is a hero in most of the sense, is far from perfect or has at least one glaring flaw.

still I think they went over board with that CGI movie for beowulf.

Ken is gonna need a lot of sake after this. Hope they got a secret stash somewhere.

I find that it’s easier to separate the artist from the artwork – nobody’s perfect, and artists tend to be pretty miserable in real life – with all sorts of problematic behaviors (drugs and alcohol being the least, and abusive behavior – from being generally a harmless jerk to being a full on rapist). I still like Alice in Wonderland even after I found out about those pictures that lewis carrol took. I can listen to music from wife-beaters and enjoy movies from questionable directors and actors. The more there are out there, the easier it is to disconnect – just because I know that if I don’t put up with it, there will be nothing left (almost).

Things are getting better – slowly – but they do come out to the light more recently. The behavioral norms are changing, and the people now doing art – they are better behaved than their predecessors.

It’s important to condemn the act that we don’t approve of – but there’s no point in throwing out the art from the same man at the same time.

You’re better off banning a movie like Ben-hur for the fact that several horses were actually killed during the original shooting – than banning an artwork that has a good message – even if the ceator of that artwork wasn’t a good man.

BTW – if it helps – while the rational mind says “this is a child”, the lizard brain says “she is sexually ready, let’s have sex” – and too many people are really bad at controlling their lizard brain.

*reads your comment on Nobuhiro* Wait – whuu??? No way! D: So we won’t get to see the new manga finished then? That is soooo sad. :((((

Well, I have a lot of mixed feelings about it, but apparently Shounen Jump does not. They’ve already released a statement that they will continue to publish the new Kenshin arc.

Well, that’s something they can build on.